“Mom, come and look what we found here…two eggs. Can we take them home?”

It was July 22, 1975, and I was 10. I was in the Planckendael Zoo, in a rural area near Mechelen, Belgium. I was with my parents, my brother and two sisters. I’ve always loved animals so I loved the zoo. Even though the Planckendael Zoo didn’t have as large a variety of animals as the downtown Antwerp Zoo, it was always fun to go there because it was less crowded and had more space both for the animals and the visitors to walk around.

Now, in the early evening, the number of visitors was dwindling. Our family was strolling in the direction of the exit, but we still paused when we passed a new exhibit. My mother was pushing the stroller with my 3-year-old sister, An, over the gravel path alongside the ostrich enclosure. My brother Erik and I still had some energy left, and we were running around the old willow trees that lined the walkway.

All of a sudden, my eyes caught something.

“Hey, let’s take a look there!” I said to Erik. I pointed to one of the oldest trees that was partially hollow. It had an aperture just above its roots, on the far side of the walkway. Hollow trees had always caught my imagination because fairytale stories suggested that mysterious creatures can inhabit them. I bent over to take a closer look, and I noticed to my surprise a rudimentary nest of straw and leaves. In the center were two white eggs. My heart started beating faster. I had little doubt that these were chicken eggs, because there were many free-roaming chickens throughout this zoo, and the eggs where the same size and shape as the ones we got from our two chickens at home.

I looked around, and didn’t see any hen nearby. The situation suggested that these eggs were abandoned. An idea popped into my mind. I ran quickly back to my mother.

“Mom, mom, come and see what we found here…..two eggs. Can we take them home? Can we put them under our chicken at home?”

After some discussion and a few seconds of thinking, my mother replied “Yes, okay, you can take them.”

I ran back to the tree, squatted down, and carefully reached in to remove the two eggs from the nest. They were cold. I walked carefully back to my mother. She wrapped them in soft napkins and placed those in an empty cardboard cookie box. That way we smuggled the two eggs out of the zoo.

As my father drove us home, I was sitting in the Volvo’s back seat holding the box and thinking of the two eggs, and of the two bantam chickens that we had at home. The brown speckled hen tried to brood frequently, even though we usually removed the eggs. We did not have a rooster at home, but only a male pheasant (which mounted the chickens frequently for mating). But even when a year earlier we had allowed the hen to incubate some of those eggs, none had ever hatched, suggesting that crossbreeding chickens and pheasants was not that easy. For the past few weeks, that brown-speckled hen had been brooding again stubbornly. But with the discovery of these two eggs in a zoo with plenty of roosters, there was a fair chance that these two eggs were fertilized. This presented an opportunity of a life-time: to get some baby chicks!

The drive home felt twice as long as usual. When the sun was slowly fading away behind the trees, our car finally pulled into the garage. I carefully stepped out of the car and with my box of fragile treasures, I walked toward the backyard. Underneath the concrete stairway that ran along the backside of the house was a small aviary that housed our two chickens, the male pheasant and some parakeets. I walked in and was happy that the hen was still sitting in the wooden nest box on the ground. I opened the cardboard cookie box and surreptitiously hid an egg in the palm of my hand as I reached into the nest box. While the back of my hand was being pecked by her sharp beak, I replaced the infertile but warm eggs with a new cold egg. I repeated this procedure with the second egg. The hen immediately accepted them. I quickly stepped out of the aviary, locked the door, and released a sigh of relief. Now their fortune was no longer in my hands. I went back into the house, with a feeling of satisfaction and hope – hope that the chicken would continue to brood for three more weeks, and that the eggs had been fertilized and were going to develop.

The next few weeks were an exercise in patience. Whenever I went outside to feed the animals or to play in the back yard, I peeked in to make sure the was incubating the eggs well. And for 16 days I was at peace, because the chicken was doing what she was supposed to do: incubating the eggs carefully, and once or twice a day taking a short break. And with each passing day, the anticipation kept growing.

But on day 17, I noticed that the chicken was taking more frequent and longer breaks. This made me worry. The chicken might have been thinking “I’ve been incubating now for more than 6 weeks, this is too much, I’m getting tired of this so I’m giving it up.”

When I felt her breaks were too long, I would put her back on the nest, and she would incubate for a while, but then she would leave the nest again a while later. This was not normal. I went to tell my mother about my fears.

“ Don’t worry, there isn’t anything we can do. Just trust nature, ” she said.

Later that evening, as darkness was setting in, I noticed the chicken had left its nest again and was on a higher perch, as if ready to go to sleep there. I took her down and put her back on the nest. I kept my hand on her back for a minute, and hoped that she would believe me when I whispered: “These are not your own eggs. These eggs are probably fertilized so there’s a really good chance that if you continue for four more days, they will hatch. Please don’t give up now.” I waited quietly until it got quite dark, but eventually I had to return to the house, as it was also bedtime for me. That night, I did not sleep well, but I prayed for a good outcome.

The next morning when the sun pierced the curtains of my bedroom, I woke up, jumped in my clothes and ran downstairs. My worst fears turned out to be true, as the chicken was walking around, and was not even making the typical “clucking” sound that indicates she was brooding. I touched the eggs….they felt stone-cold. I took them in my hand to give them some warmth, and then ran up the stairs to my mother in the kitchen.

“Mom, the chicken has totally given up, the eggs are cold. We have to do something. We have to warm them up.”

“But this is very difficult,” she replied.

“You need a special incubator. It’s not that simple. We don’t know what the eggs need.”

“Wait, I have a book,” I replied. At my 8th birthday party, a friend had given me a book about chickens. I remembered that one of the chapters had described the process of artificial incubation with details on temperature, humidity and the need to turn the eggs in the incubator. I handed the eggs to my mother and ran upstairs to my bedroom to retrieve the book. With my heart beating fast, I found the page on incubation and showed it to my parents. My father, a photographer, knew exactly what to do.

“In my dark room, I have a special lamp that gives much heat,” he said. “And I have a dimmer knob to regulate the intensity. “

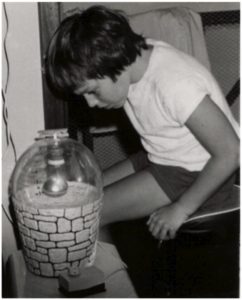

My parents became as excited as I was. I took the eggs again in both my hands, hoping that some of my warmth could make a difference. My dad came back a few minutes later with the heat lamp, and a large glass sphere; it was an old kitchen water boiler. My mom showed up with a large plastic flowerpot. We placed some hay on the bottom of the pot, carefully placed the eggs in the center, positioned a sensitive thermometer next to them, and an egg-cup filled with water for evaporation. We placed the glass sphere and the heat lamp on top of the flower pot. We plugged it in, and the light came on. Soon we saw the temperature climb. With frequent adjustment of the dimmer knob, we were able to get the temperature quite stable. Voila, there was our improvised egg incubator, and it worked! Now it was just a matter of monitoring the system regularly to make sure the temperature remained on target, turning the eggs twice daily, being patient and keeping up hope. At night, my parents took the incubator to their bedroom so that they could check on it. They probably knew that if they left it in my room, I wouldn’t be sleeping much.

Two days later, I woke up and ran downstairs in my pajamas to the living room to check on the incubator. Carefully I lifted up the glass sphere and placed it next to the flowerpot. I was turning the two eggs, when suddenly I heard a chirping sound. I looked around, and didn’t see anything, as my siblings were still sleeping, and only my mother was in the kitchen, preparing breakfast.

“Mom, come quickly. There is some sound.” I held one of the eggs near my ear. My eyes opened wide and my breathing halted for a few seconds.

“The sound is coming from the egg, I can hear it. Here, you listen to it!” I said excitedly, as I held the egg near my mother’s ear. She nodded. I placed the egg back, and took the 2nd egg to hold it near my ear.

“I don’t hear anything at all now, but that confirmed it – the first sound came from that first egg, that’s for sure.”

I had placed the glass sphere back onto the flowerpot and did a victory dance around the table. Yes, yes, yes, there was definitely a live chick in the first egg!

I had read that even after the chick has pierced the air chamber and starts breathing, it can still take a day or so before it hatches. But to make sure I wouldn’t miss anything, I decided to stay home for the rest of the day. Every few minutes, I looked through the glass of the incubator and searched for any sign of a crack in the shell. Finally, in the evening, a tiny crack was noticed. My parents moved the incubator to their bedroom, and I asked them to wake me up if something changed. I slept poorly.

I woke up when my shoulder was gently grabbed. “Koen, come and take a look,” called my mother at about 1 am. I jumped out of bed. A small chip of the egg shell had fallen off. The chirping sound was stronger, and accompanied briefly by the moving tip of a tiny beak.

My father took a few pictures, but the chick must have grown tired, because nothing else happened for a long time, and my parents went back to sleep. For the next few hours, I sat quietly on the chair that my mom had placed next to the incubator. Bending forward, I monitored diligently the eggs in the spherical glass incubator. A few times, my 6-year-old sister Kristel came to take a peek, stayed a few minutes and then quietly disappeared back to her bedroom.

The brief moments of exciting activity and chirping were interspersed with long periods of silence that tested everybody’s patience but mine. Slowly, over the course of several hours, the small crack grew into a zigzag line. Occasionally I stretched my back and yawned. Slowly, painfully, the zigzag line encircled more than half of the egg. The egg trembled once in a while, and I could just envision the chick trying to push the cap from the egg, but it wasn’t making much progress.

With the dawn came success. I remember the date: Aug. 13, 1975. With the first light, the chick managed to push aside the two egg shells and crawled out, looking totally wet and disoriented.

Chirping loudly, it looked me in the eyes. After a few minutes of mutual admiration, the chick fell asleep and I crawled back into my bed, feeling very satisfied and humbled by this experience. Although millions of eggs have hatched daily for millions of years, this particular chick is the one that made me understand how precious and wonderful life truly is.

When I got up a few hours later, the chick was awake. Its down had dried and it was fluffy all over, yellow with brown stripes over its head and its back. I felt I had never seen such a cute animal.

That morning, my father and I went to the pet store to buy some special chick feed. Later that day, we moved the chick into an old hamster cage. Above the hamster cage we mounted another heat lamp and then placed this new home on a small table next to the couch in the living room. The 2nd egg was still being incubated, but when we opened it a few days later, we found a mature dead chick.

The surviving chick was named Pats, after a cartoon boy hero from the children’s section of the newspaper. I did not grow tired of observing Pats walking around in his new home, chirping, eating, and frequently taking short naps. Those first 2 days, everything was just perfect.

The following morning, I woke up. As usual, I would hurry up and run downstairs to the living room to check on Pats. This time, however, I looked at the chick and my smile disappeared.

“Mom, I think something’s wrong with the chick. It doesn’t look as healthy and alert anymore.”

My mom, who was raised on a farm and was familiar with chickens, also suspected that something was wrong. But she didn’t want to worry me.

“We just have to wait and see what happens,” she said.

But that didn’t satisfy me, as I noticed hourly that things were not improving. Reading through my now well-thumbed chicken book, I felt quite sure that the symptoms matched those of Salmonella pullorum, which is a bacteria that can live in the ovaries of the hen, and is transmitted to the egg. It is usually fatal within a few days after birth because in addition to causing intestinal problems, it spreads throughout the chick’s whole body. Except for wiping off its cloaca regularly to remove the sticky feces, and putting some drops of water in its mouth, I felt frustrated not knowing what more to do. My father made a phone call to a veterinarian, who had said that were was nothing that could be done about it. The chick never received any antibiotics. I felt miserable and stressed. I wondered if perhaps I was just stuck in a bad dream, and the only way to escape was to try to fall asleep and then wake up to a whole different situation.

The following morning, there was no sign of improvement whatsoever. In fact, the situation looked more bleak, as Pats had even less energy, no interest to eat, and wasn’t even chirping anymore when it saw me. Tiny baby chicks don’t have much energy reserves so the loss of appetite was very worrisome. In the late afternoon, the chick stopped walking, and couldn’t even stand up anymore. So I knew that its time had come. This was the worst day in my life. What could I do?

Being raised in a Catholic family, and attending a Catholic school, I had learned of the seven sacraments, including the “Last rites/ Anointing of the sick” – a ritual given to those severely ill and often near death. I felt this innocent chick deserved this final blessing. But even at age 10 I didn’t think a priest would come to our home to anoint a dying chick.

I remembered we had something else that could perhaps be a suitable substitute. We had holy water from Lourdes. Lourdes is a holy site in France where the Virgin Mary appeared numerous times to a peasant girl named Bernadette. The legend goes that upon request of the Virgin Mary, Bernadette started digging in the soil and a well had sprung, of which the water had miraculous healing powers. My aunt Yvonne went regularly to Lourdes and had brought us such holy water in a transparent plastic bottle shaped like the Virgin Mary. I knew exactly where it was. I rushed upstairs to my bedroom to grab the bottle from the bookshelf and returned in panic, for now the chick was lying flat on the bottom of its cage with its head stretched out and breathing heavily, gasping for air. It was now or never.

I burst in tears. With shaking hands I unscrewed the blue cap (which was in the shape of Mary’s crown) and poured a few drops water into the bottle cap. I used a pipetter to draw up some water, and then released a few drops over the chick’s head. A bit of the water ran down along its beak. Tears were streaming down my face, and I was sobbing heavily.

My eyes were so swollen with tears that I couldn’t see, so I folded my hands together and kneeled on the couch. I prayed with all my heart and soul to God, and asked God to only listen to me once in my life and have mercy on this innocent creature. We had already overcome so many hurdles. If he would hear me, I’d make up for it somehow.

Minutes later, completely drained of tears and emotion, I bent over for another look at the chick, expecting it to have passed away.

However, I noticed it was breathing more slowly again, and after a few seconds, it lifted its head, and made a chirping sound, the first time it had chirped that day.

“Mom, mom, come quickly!”, I yelled, my heart thumping.

My mom rushed from the kitchen into the living room. She and I watched as Pats continued to perk up by the minute. Within half an hour, it was walking again, just like any healthy chick. It also started to peck hungrily at the chick feed. I couldn’t believe what I had observed. I was speechless. It wasn’t a dream, it was reality.

From then on Pats continued to develop normally, as if no disease had ever occurred. On warm sunny days, I would take Pats out into our garden, and he would follow me across the lawn. Pats thought I was his mom. He grew up to become a healthy rooster and went to live with the chickens.

Seeing this special bond, my parents encouraged me to write down the story of how we saved the abandoned egg by placing it under a heat lamp. We decided not to mention a single word about the disease and the Lourdes water, as we didn’t want to create any controversy. I submitted the story to a children’s television news program and also to the weekly children section of a big Belgian newspaper. Both media outlets reported our story, which was for me a special moment, and a first introduction to publishing something.

The connection I shared with Pats remained very precious, something like the bond central in the 1982 movie “E.T.”.

While I avoided spending time on an explanation, this whole experience gained significance especially towards the end of my high school years, when as an emotionally troubled and insecure teenager, I stood at the crossroads of different pathways of higher education. Contrary to what one might expect, there was no interest or any ambition whatsoever to pursue some religious career. Instead I decided to start the studies of Veterinary Medicine at the University of Antwerp in 1983. In fact, it wasn’t really a major decision, it just felt like it was the only right thing to do.

I was in my 2nd year of veterinary school, in December 1984, when Pats became very ill of old age. I brought him indoors. He spent his last few days in a cardboard box on my bedside, before he died silently one night. His children and grandchildren survived in my parents’ garden into the early ‘90s.

Now in 2011, while I live in the USA, the bottle with holy water from Lourdes, 36 years after it was last opened, still stands on the bookshelf in my bedroom in Belgium. Despite my professional career as veterinary doctor and researcher of infectious diseases, I am still not able to explain scientifically what occurred to the baby chick on that particular August day in 1975.

I keep asking myself: “Was it a coincidence? Or was it a miracle? Did some higher existence, however one calls it – God, a supreme being – watch over me, did me a favor, and had special plans for me? If so, why me? “

One thing is sure: I never regretted becoming a veterinarian.